Building A LLM From Scratch with Wolfram Language

Inspired by Raschka’s book on building a large language model from scratch, we implemented our own version using the Wolfram Language (WL). We opted for WL over Python due to its higher level of abstraction, rich set of built-in functions, and powerful computational capabilities, which streamline the development process.

Model Architecture

The architecture of the LLM is shown in Figure 1. The model takes an input sequence. which is first transformed into vectors through token and position embeddings. This sequence passes through multiple transformer blocks and a feedforward block that outputs a vector of vocabulary size. Finally, a softmax layer generates the model’s prediction.

Our model uses four transformer blocks, as seen in Figure 2.

As shown in Figure 3, the transformer block includes an attention layer and a feedforward lock. The attention layer uses causal masking to prevent the model from examining future tokens. Normalization layers are placed before and after the attention layer to improve stability and performance. The feedforward block uses Gaussian Error Linear Unit (GELU) activation and consists of two linear layers. Two dropout layers reduce overfitting during training. The transformer block has two residual connections to reduce the vanishing gradient problem.

Here are the specific settings used for the model:

- Embedding Dimension: $128$

- Number of Attention Heads: 4

- Number of Transformer Blocks: 4

- Dropout Rate: 0.1

- Dimensions of linear layers in the feedforward block: (128, 4$\times$128) and (128, 128)

- Context Size: 50

The following code outlines the model implementation in Wolfram Language:

config = <|

"vocab_size" -> 1186,

"context_size" -> 50,

"n_transformers" -> 4, (* number of transformer blocks *)

"dim" -> 128, (* size of input to transformer block, output, embedding dimension *)

"nHeads"-> 4, (* number of Heads *)

"dropout" -> 0.1, (* drop out rate *)

"feedforwardsize" -> 4 (* feedforward block layer sizes {4*dim, dim} *)

|>;

TransformerBlock[cfg_] := NetGraph[

<|

"norm1"->NormalizationLayer["Biases"->None, "Scaling"->None],

"key"->NetMapOperator[LinearLayer[{cfg["nHeads"], cfg["dim"]/cfg["nHeads"]}]],

"query"->NetMapOperator[LinearLayer[{cfg["nHeads"], cfg["dim"]/cfg["nHeads"]}]],

"value"->NetMapOperator[LinearLayer[{cfg["nHeads"], cfg["dim"]/cfg["nHeads"]}]],

"attend" ->AttentionLayer["Dot", "MultiHead"->True, "Mask"->"Causal"],

"flatten" ->NetMapOperator[FlattenLayer[]],

"norm2"-> NormalizationLayer["Biases"->None, "Scaling"->None],

"total1"->TotalLayer[],

"total2"->TotalLayer[],

"dropout1"->DropoutLayer[cfg["dropout"]],

"dropout2"->DropoutLayer[cfg["dropout"]],

"feedforward"->{

NetMapOperator[LinearLayer[cfg["dim"]*cfg["feedforwardsize"]]],

ElementwiseLayer["GELU"],

NetMapOperator[LinearLayer[cfg["dim"]]]

}

|>,

{

"norm1"->{"key", "query", "value"},

"key"->NetPort["attend", "Key"],

"query"->NetPort["attend", "Query"],

"value"->NetPort["attend", "Value"],

{NetPort["Input"], "attend"->"flatten"->"dropout1"}->"total1"->"norm2"->"feedforward",

{"flatten", "feedforward"->"dropout2"}->"total2"

},

"Input"->{"Varying", cfg["dim"]}

]

LanguageModel[cfg_]:=

NetGraph[

<|

"token_emb" -> EmbeddingLayer[ cfg["dim"], cfg["vocab_size"]],

"pos" -> SequenceIndicesLayer[],

"pos_emb" -> EmbeddingLayer[cfg["dim"], cfg["context_size"]],

"total" -> TotalLayer[],

"transformers" -> Table[TransformerBlock[cfg], cfg["n_transformers"]],

"classify" -> NetMapOperator[LinearLayer[cfg["vocab_size"]]],

"softmax" -> SoftmaxLayer[]

|>,

{

{"token_emb", "pos"->"pos_emb"}->"total"->"transformers"->"classify"->"softmax"

},

"Input"->"Varying"

]

llm = LanguageModel[config];

Training and Results

Text Data

As Rascha did in his book, we use Edith Wharton’s short story, “The Verdict,” to train the model. The text is relatively short and allows for quick training. The text is split into $7652$ words, and a vocabulary of $1186$ unique words is generated:

text = Import["verdict_text.txt"];

words = StringSplit[text, WordBoundary];

vocabulary = Union[words];

The words are encodeed into integers, and the dataset is partitioned into sequences of $50$ tokens with an offset of $1$:

encoder = NetEncoder[{"Class", vocabulary}];

wordsEncoded = encoder/@words;

d = Partition[wordsEncoded, 50, 1]; (* context size = 50, offset=1 *)

The context size of our model is $50$, which refers to the number of tokens in the input. When partitioning the input into neighboring sublists, the elements in the second sublist are shifted by one pisition to the first sublist. For example:

\[\{1,2,\cdots,49, 50\} \rightarrow \{2,3,\cdots, 50,51\}\notag\]Here, the first sublist serves as the input to the LLM, and the second sublist represents the target output.

Training

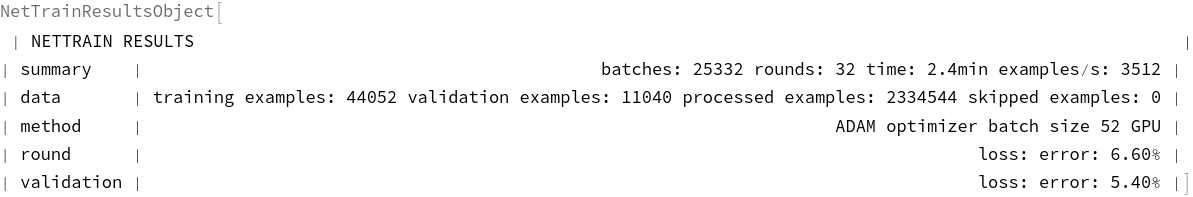

The following code trains the model using the ADAM optimizer with cross-entropy loss. $20\%$ of the data are allocated for validation.

result = NetTrain[llm, Most[d]->Rest[d], All,

MaxTrainingRounds->20,

ValidationSet->Scaled[0.2],

TargetDevice->"GPU"]

Figures 4 and 5 show the loss and error rate over the training epochs.

Text Generation

Once trained, the model can generate text from a given prompt. The following code generates new text from a promt using the trained model. The prompt text is first split into words, encoded into integers, and then fed into the model. The last word of the model output is the generated word, which is appended to the previous prompt to form the new input. This process is repeated to generate a sequence of words.

model = NetChain[{result["TrainedNet"], SequenceLastLayer[] },

"Input"->NetEncoder[{"Class", vocabulary}],

"Output"->NetDecoder[{"Class", vocabulary}]]

(* generate text*)

generateText[model_, temperature_, initText_, length_]:= StringJoin@Nest[Append[#,

model[#, "RandomSample"->{"Temperature"->temperature}]]&,

StringSplit[initText, WordBoundary], length]

The temperature parameter controls how the next word is selected from the vocabularry. When temperature is greater than zero, all words in the vocabularty have a non-zero probability of being selected, with the probability distribtuion governed by the softmax of the model’s output values. Specifically, the probability $p_i$ of selecting word $i$ is given by:

\[p_i = \frac{\exp(x_i/T)}{\sum_i \exp(x_i/T)}, \notag\]where $x_i$ are the model’s output logits, and $T$ is the temperature.

- High tempurate ($T>1$): Results in a more uniforma distributution, making the selection of a broader range of words more likely.

- Low temperature ($T\rightarrow0$): Causes the model to favor the word with the highest probability, i.e., the most likely word according to the model.

As $T$ increases, the distribution becomes more flat, leading to more diverse and unpredictable word choices. When $T=0$, only the word with the highest softmax value is selected.

The table below shows text generated with the initial prompt “What is” for different temperatures:

| Temperature | Generated Text |

|---|---|

| 0 | What is the honour being mine–oh, I was princely, my dear Rickham! I was posing to\, > myself like one of my own sitters. |

| 1 | What is that, with such such consummate skill, he managed to divert attention from the\ > real business of the picture to some pretty irrelevance |

| 1.5 | What is I think he was dead.” “You?” I must have pictures too have three years years of go go a note taken of |

| 3 | What ismight, always’re “keep been pictures.” Don’t let her sent in all advanceever have painted (humoured surprisedamask of and it!” Only |

As temperature increases, the generated text becomes more “creative” and less predictable. With temperature is $0$, the generated text closely resembles the original training data.

Conclusion

A large language model with attention is built from scratch using the Wolfram Language. The architecture of the model is surprisingly simple, as thoroughly explained in Raschka’s excellent book. The implementation in Wolfram Language is straightforward, thanks to its high-level abstractions and flexibility.

Although the training dataset is relatively small, the generative capabilities of the trained model are clearly demonstrated. Larger training datasets will undoubtedly enhance the model’s performance. This project serves as both a tool for understanding large language models and a foundation for future projects involving more complex architectures and larger training corpora.

References

Raschka, S. (2024). Build a Large Language Model From Scratch. Manning.

Epigule-Pons, J. (2023). Shakespearean GPT from scratch: create a generative pre-trained transformer. Retrieved from Wolfram Community